This is the first of two notes on Ancient Greek mathematics. Math has always been propelled forward by abstraction, and one of the first abstractions was from geometry (where the idea of quantity is described by measurement) to arithmetic (of abstract numbers which do not measure anything in particular). To the Ancient Greeks, this abstraction was more fresh than it is for us, so they were fascinated by numbers that represented geometric figures.

These include the familiar square numbers and triangular numbers

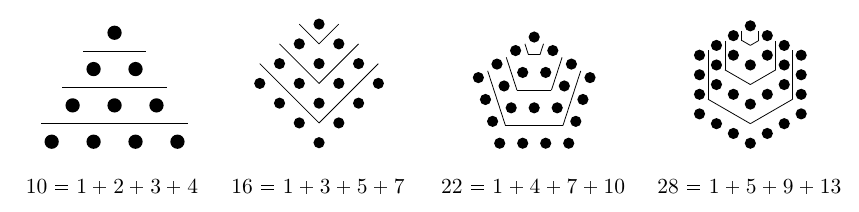

as well as pentagonal and hexagonal numbers and so on:

In the top figures, the polygonal numbers are partitioned into what the Greeks called gnomons (originally a name for an L-shaped carpenter’s tool). The gnomons for triangles have size , for squares have size

, and in general the gnomons are an arithmetic sequence starting with

, with common difference

. So the

-gonal numbers, the gnomons are

. Therefore,

Definition. A planar number is a whole number represented as either a polygonal number or a rectangle (product of two integers ).

In modern terms, a planar number is not a number itself, but rather a number together with a geometric representation. For example, can be represented as a planar number in five ways: as rectangles

and

, the seventh triangular number, the fourth pentagonal number, or the first

-gonal number.

Theorem. There are infinitely many numbers which are both triangular and square:

This famous fact is proven using Pell equations (see here).

Problem 1. Are there numbers which are both triangular and pentagonal? Square and pentagonal? -gonal and

-gonal? If there is one such number, are there always infinitely many?

Problem 2. Every positive integer is trivially polygonal because it is the first

-gonal number. What proportion of positive integers are non-trivially polygonal?

These problems range a lot in difficulty. Problem 2 is one that I don’t know the answer to. If you can answer this or one of my other hard problems, please let me know!

Triangulations of polygons

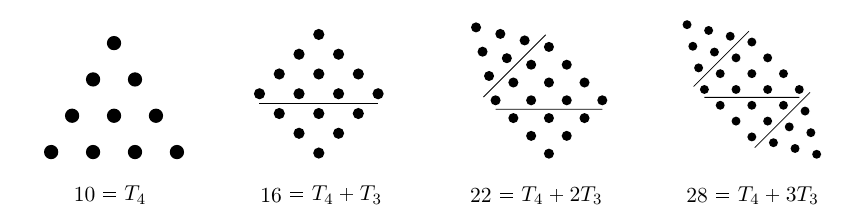

In geometry, every -gon can be triangulated by

triangles. (This is an important fact — we can use it to calculate the sum of the angles in a polygon!) Miraculously, the same is true in arithmetic. Every

-gonal number is a sum of

triangular numbers!

In general, the -gonal number is

. This is also

, which can be expressed in modern notation as

.

Modern mathematicians have tended to view polygonal numbers as an idle curiosity, or a part of recreational math. But they are actually the two-dimensional case of the beautiful and useful theory of integer-valued polynomials.

Let’s start by reasoning like the Ancient Greeks. If polygonal numbers can be built out of triangular numbers just as all polygons can be triangulated, then since all polyhedra can be partitioned into tetrahedra, it stands to reason that polyhedral numbers can be built out of tetrahedral numbers . And more generally, we might guess that

-dimensional numbers can be built from the

-simplex numbers

. In a sense, this would be exactly right! Let me explain.

A polynomial is integer-valued (see here) if

is an integer for all integers

. For example,

is integer-valued even though it doesn’t have integer coefficients.

Theorem. A degree polynomial

is integer-valued if and only if there are integers

with

such that

where

. The integers

are unique.

Example. The quadratic integer-valued polynomials which satisfy and

are just

, which precisely represent the polygonal numbers.

Example. Since is integer-valued, we know we can express

. Another useful expression is

. Therefore, cube numbers are sums of six tetrahedral numbers, just as geometric cubes can be partitioned into six tetrahedra. If the

tetrahedral number is

, then

.

Problem 3. For any nonnegative integers , the functions

are sequences of

-dimensional numbers. Express the

-dimensional hypercubes as a sequence of

-dimensional numbers. Which integer-valued polynomials of degree

can be expressed as sequences of

-dimensional numbers?

For all you who believe that math is only interesting if it is deep, integer-valued polynomials are also connected to some very modern mathematics via algebraic topology. The K-theory of infinite-dimensional complex projective space is the ring of integer-valued polynomials. If this makes any sense to you, then see if you can describe the multiplicative structure of the ring. In simple language:

Problem 4. The product of two integer-valued polynomials is an integer-valued polynomial. If the original polynomials are expressed in the form , how can you express their product in this form? For example, find the coefficients:

An oblong oddity

As we have said, the triangular numbers are the building blocks of two-dimensional numbers, in the same way that all two-dimensional polygons and surfaces can be triangulated. Moving to three dimensions, the tetrahedral numbers

should be the building blocks of three-dimensional numbers, whatever those are, and so on. (Yes, the building blocks of geometric numbers and integer-valued polynomials are the terms of Pascal’s triangle!)

So in the same way, the counting numbers should be regarded as the basic one-dimensional numbers. Now here is a very familiar one-dimensional definition and its two-dimensional analogue:

Definition. A whole number is odd if it is the sum of two consecutive counting numbers or even if it is the sum of a counting number with itself. (Side note: Since the Greeks started counting at , this definition has the curious side effect that

is neither even nor odd, although they did say that it was odd in a more abstract sense, ‘odd in potential’.)

Two-dimensional analogue. The sum of two consecutive triangular numbers is a perfect square, while the sum of a triangular number with itself is an oblong number, which is a product of two consecutive whole numbers and therefore a rectangular (planar) number.

According to the dualism of the ancient Pythagoreans (who were philosophers and mystics as well as mathematicians), this made the sequences of square and odd numbers related and opposed to the sequences of oblong and even numbers. (The square and odd numbers had a positive connotation, and the oblong and even numbers a negative connotation.)

There is yet another connection between odd and square numbers, even and oblong numbers. The squares are the sums of the first odds, and the oblongs are the sums of the first evens:

The Greeks would have said that the odds are the gnomons of the square numbers, and the evens are the gnomons of the oblong numbers! So what happens in three dimensions? The analogue of the (positive) odd and square numbers are the square pyramidal numbers and just as the odds are gnomons of the square numbers, so the squares are gnomons of the square pyramidal numbers. That is,

and so we see that all these classic facts about sums are really about 2D and 3D numbers. For example, the sum of squares formula is the algebraic version of the decomposition of a square pyramid into two tetrahedra.

Let’s examine this more closely. We have

- odd numbers

,

- square numbers

,

- square pyramidal numbers

,

and so the fact that odds are gnomons of squares and squares are gnomons of square pyramids can be expressed and

. These formulas are no accident; they are examples of the:

Hockeystick Identity

So how is any of this useful? Suppose we want to sum a polynomial, like . By the theory of integer-valued polynomials, we can express the polynomial as a sum of binomial coefficients,

or

. Then we can use the Hockeystick Identity to sum instantly!

, which is

. Alternatively, since a cube is a sum of six tetrahedra

, then

. Geometrically, since a cube is a sum of six tetrahedra, a 4D cubical simplex is a sum of six 4D-simplices.

Problem 5. Find the coefficients .

We will end with the answer to this problem. It is enough to express in terms of binomial coefficients. It turns out this can be done in terms of the Stirling numbers of the second kind (see here):

. Therefore,

[…] is my second note on Ancient Greek mathematics, following last year’s post on planar numbers. At the time, I had just read Introduction to Arithmetic by Nicomachus, written around 100 AD. I […]

LikeLike