I recently rediscovered some fascinating math after looking at Ancient Roman floor tilings:

floor tilings, early Roman empire

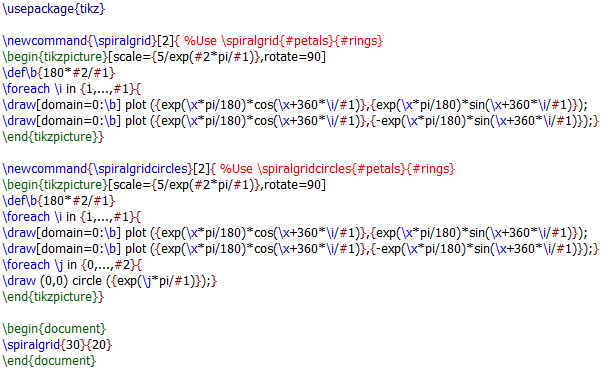

Aside from the heads of mythological figures in the center, what do you notice about these designs? The first thing I notice is that they are made from the same triangular tilings with different coloring schemes. Since their sides are not straight lines, the tiles aren’t technically triangles. However, each tile does have three angles, which are always 45, 45, and 90 degrees.

This is no illusion. It is actually mathematically possible to construct a spiral tiling of 45-45-90 triangles!

Notice that each spiral, one of which is highlighted above, must intersect each of the concentric circles at a 45 degree angle. This allows us to formulate a mathematically precise problem:

Problem. Find a curve which intersects each circle centered at the origin at a 45 degree angle.

Those who have worked with calculus enough may recognize this word problem as a differential equation in disguise, since we are asked to determine a curve given information about its tangent lines. Because of the radial symmetry of the diagram, and because the desired curve looks like some kind of spiral, it will be much easier to use polar coordinates, . Alternatively, we may parametrize

Now at the point , this intersects the circle

, and they should intersect at a

angle. Using the dot product formula

we can reduce (exercise) to , the most basic of all differential equations! Apparently, our desired curve is

.

Definition. A logarithmic spiral is a curve , which may be rotated, dilated, or reflected. In complex numbers,

, for any complex number

.

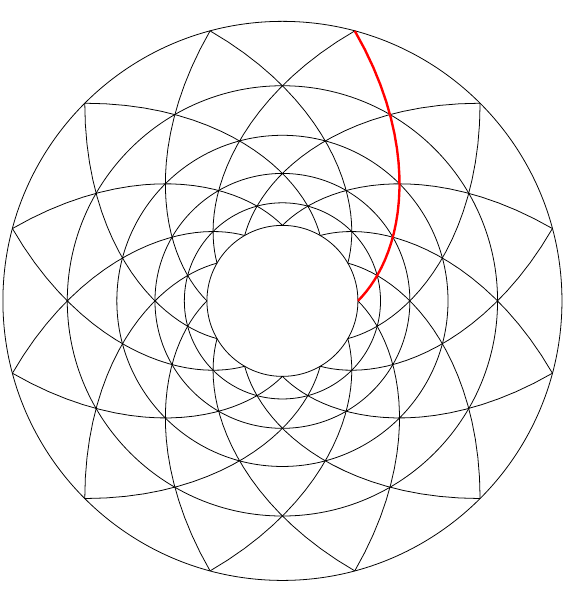

The Roman tiling is made up of equally spaced logarithmic spirals in each direction, clockwise and counterclockwise. If these are graphed without the concentric circles, they form a system of curves, each of which intersect at right angles. This is an orthogonal lattice. If logarithmic curves in each direction are graphed, we see what looks like an

-petaled flower:

three orthogonal lattices

In Cartesian coordinates, we are used to the orthogonal lattice called a rectangular grid. But there is also an orthogonal lattice in polar coordinates, the lattice of logarithmic spirals shown by the Romans in their art!

Since we have no record of the Romans understanding differential equations or even the exponential function, I wonder: Just how much of the mathematics of this configuration did they understand?

References

Read about other neat history and applications of logarithmic spirals here: https://mathcurve.com/courbes2d.gb/logarithmic/logarithmic.shtml

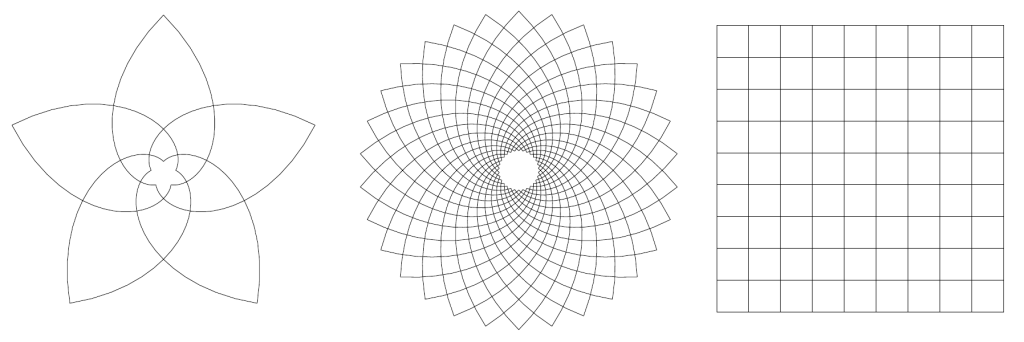

I generated these pictures using the LaTeX package Tikz. You can too, with this code: