This is my second note on Ancient Greek mathematics, following last year’s post on planar numbers. At the time, I had just read Introduction to Arithmetic by Nicomachus, written around 100 AD. I hoped to learn a little about the history of math, but I didn’t expect to learn any actual mathematics. However, I am always amazed at how much math is out there! I was surprised to learn about a whole theory of mean progressions that has been largely forgotten (at least to my knowledge).

The familiar means

The Pythagoreans (the Ancient Greek mystics who used math and music theory to worship the gods) were interested in sequences of positive real numbers for which the ratio

is equal to the ratio between two of

,

, and

themselves. Then they said that

was a mean progression, and that

is a mean of

and

. So why is this strange condition interesting? Because of a general principle in mathematics: If every known example of a phenomenon satisfies the same property, then that property is probably important to understanding the phenomenon! It turns out that the three most common means are all examples of this kind of mean progression, so the Greeks concluded that this property

must be important to understanding means!

For example, if is equal to the ratio

, then

, which is to say that

are in arithmetic progression or that

is the arithmetic mean of

and

. An arithmetic sequence (like

or

) is one in which any three consecutive terms are in arithmetic progression, so each term is the arithmetic mean of its neighbors.

On the other hand, if , then

, which is to say that

is the geometric mean of

and

, or

is in geometric progression. A geometric sequence is a sequence in which any three consecutive terms are in geometric progression; that is, each term is the geometric mean of its neighbors.

The Greeks were interested in infinite geometric sequences like (which is called geometric because the numbers represent a point, line segment, square, cube, etc.) but also geometric sequences like

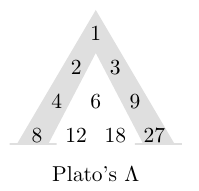

which cannot be extended in either direction using integers. In Plato’s Λ (Greek letter Lambda), each row and diagonal is a geometric sequence, and each entry is the difference of the two directly below it1.

Third, if , then

, which is the harmonic mean. Harmonic sequences like

are not quite as well-known as arithmetic and geometric sequences, but the Pythagoreans were interested in them because of their connection to music theory.

Problem 1. Prove that a sequence is in harmonic progression if and only if

is in arithmetic progression.

Problem 2. Can you find a harmonic sequence of 5 integers? 6 integers? What about a harmonic sequence of integers for any positive integer

? Among all harmonic sequences of

positive integers, which one has the smallest maximum?

The forgotten means

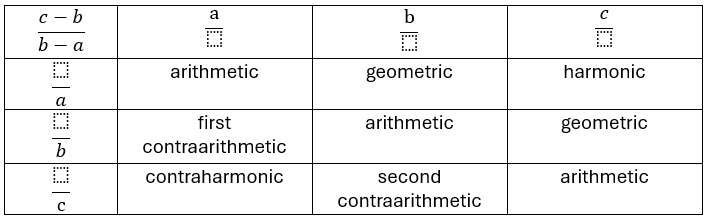

Remember: We are interested in progressions such that

is equal to the ratio between two of

,

, and

. In principle, there are nine fractions

if

and

are chosen from

,

, and

, and they correspond to six means:

implies

, the arithmetic mean.

or

implies

, the geometric mean.

implies

, the harmonic mean.

implies

, the contra-harmonic mean.

implies

, the first contra-arithmetic mean.

implies

, the second contra-arithmetic mean.

The contra-harmonic mean is so-called because it is the reflection of the harmonic mean across the arithmetic mean. In other words, the average of the harmonic mean and the contra-harmonic mean is .

Problem 3. Does there exist a contra-harmonic sequence of four integers?

I think this may be an open problem, so let me know if you solve it! For example, is a contra-harmonic sequence because

, but it can’t be extended in either direction to a contra-harmonic sequence of four integers.

Problem 4. If and

are two positive real numbers, let

denote the six Ancient Greek means — the arithmetic, geometric, harmonic, contra-harmonic, first contra-arithmetic, and second contra-arithmetic means. Prove that they always appear in the same order:

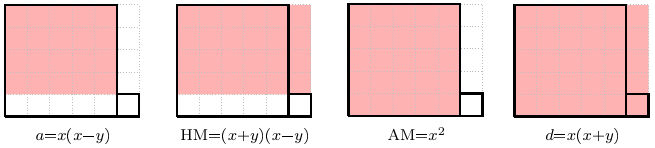

Visualizing means

Shown above are an and

square (example

and

) fitting within an

rectangle. The four rectangles containing the upper left rectangle form a sequence

where

is the harmonic mean of

and

, and

is their arithmetic mean.

The Pythagoreans considered this sequence to be especially beautiful because it connects planar numbers (in this case, rectangular) with the three most important types of mean progression: is an algebraic progression,

is harmonic, and the relation

describes a variant of a geometric progression.

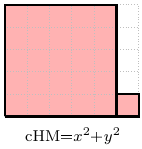

In fact, the contra-harmonic mean of and

can also be expressed geometrically:

Not nice enough to be mean

Arithmetic, geometric, and harmonic sequences all have a nice property that I call the subsequence property2: If is a sequence of the desired type, then so is

for any

and

. Equivalently,

is always the mean of

and

, whenever

are all defined.

Problem 5. Prove that arithmetic sequences, geometric sequences, and harmonic sequences each have the subsequence property.

The subsequence property has desirable consequences: For example, it implies that there is a simple formula for the term of an arithmetic sequence (

), geometric sequence (

) or harmonic sequence (

).

Problem 6. Prove that contra-harmonic, first contra-arithmetic, and second contra-arithmetic sequences do not have the subsequence property.

Perhaps this is one reason that these exotic means have been forgotten. As a result, it is not easy to calculate the term of a contra-harmonic sequence.

Problem 7. If is a contra-harmonic sequence where

, then what is the limit of

as

? Does the sequence go to infinity? If so, how quickly? Or does it converge to a number, in which case, can you find a formula for that number in terms of

and

? Then repeat for the first and second contra-arithmetic means.

Problem 8. The Heronian mean is used in geometry to calculate the volume of a pyramidal frustum. We might say that a sequence is in Heronian progression if each term is the Heronian mean of its neighbors. Do Heronian sequences satisfy the subsequence property? What can you say about the

term in such a sequence?

A hard functional equation

We have already started to move beyond Ancient Greek ideas, but here is a question in a very modern style: Can we describe all possible means? We should start by listing some properties that means should have:

- A mean should be a function

defined on positive real numbers

and

.

- It should satisfy

and

.

- It should satisfy the subsequence property: If

is a sequence of positive real numbers satisfying

for all integers

, then we should also have

for all integers

satisfying

.

Problem 9. Find all functions means satisfying these three properties.

Problems 3 and 9 are very difficult. Let me know if you can solve them!

- Plato’s Lambda is a visual demonstration of the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic, that every positive integer has a prime factorization. By starting with the prime powers and filling in the spaces between them using geometric sequences, all positive integers appear. Only the powers of 2 and 3 are shown in the visual. For Plato, this process symbolizes the creation of the world through geometric progression, but it also reflects how modern mathematicians think about number theory, as a progression from primes to prime powers to all natural numbers. ↩︎

- Modern mathematicians don’t usually think about means in terms of ratios like

(as the Greeks did), but rather in terms of functions. If

is an increasing function defined on positive real numbers, then

can be thought of as a mean. The arithmetic mean corresponds to

, the harmonic mean to

, and the geometric mean to

. For more, see generalized means. ↩︎